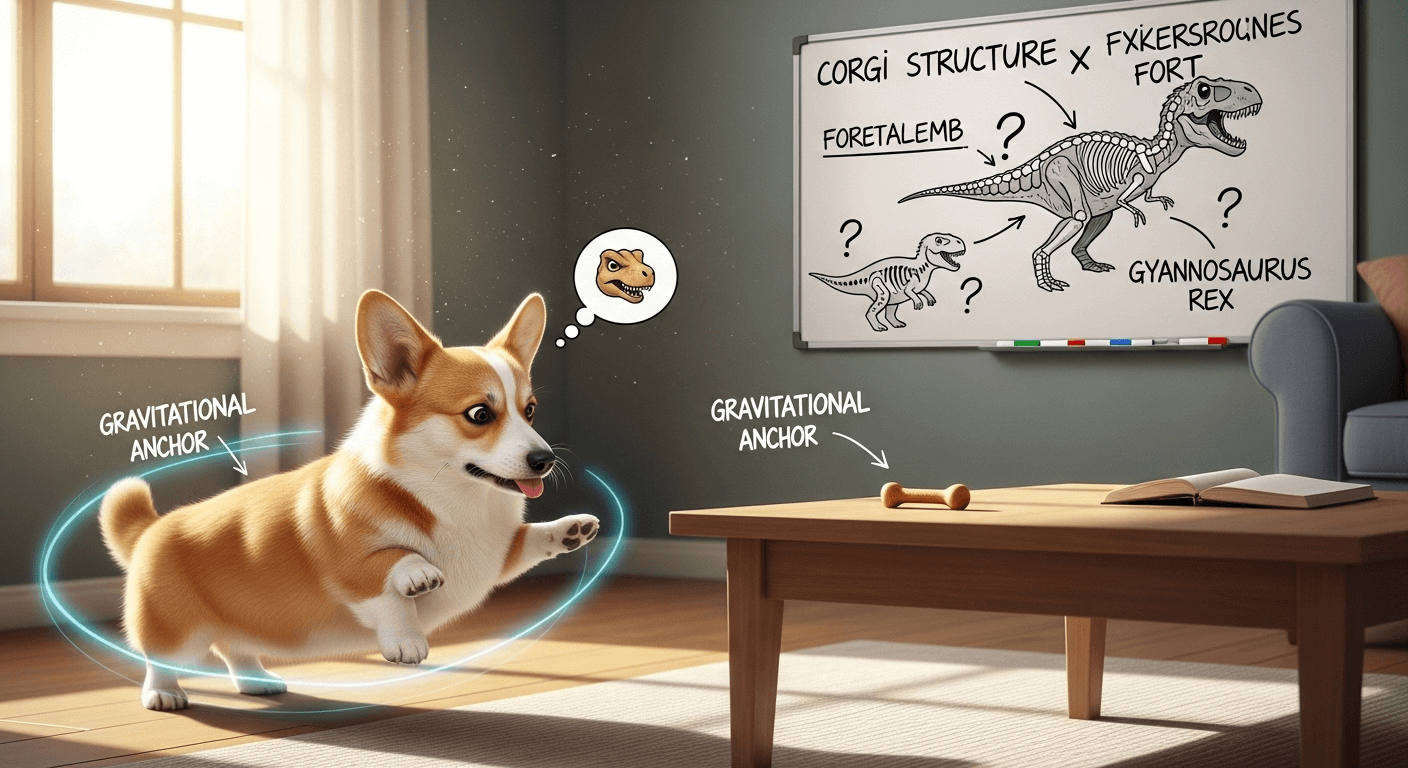

The Great Corgi Forelimb Conundrum: An Evolutionary Oopsie or a Gravitational Anchor?

Published: 2025-11-01

Let us gaze upon the modern marvel that is the Pembroke Welsh Corgi (Canis familiaris).

This creature, a sentient loaf of bread with ears, presents a biomechanical riddle that has baffled scientists and delighted internet users for decades. We speak, of course, of its tiny legs. These diminutive appendages, affectionately known as “stumps” or “drummies,” are a biological absurdity that finds its only true rival in the fossil record: the Tyrannosaurus rex, another icon famous for its comically short arms.

Today, we embark on a deeply serious, not-at-all-silly investigation to settle the debate once and for all. Are these “T-Rex arms” an evolutionary leftover, a non-feature that just never got deleted in the last software update? Or are they a masterclass in bio-engineering, a sophisticated system designed to anchor this fluffy torpedo to the very fabric of spacetime? Prepare for a deep dive into genetics, history, and physics as we unravel the mystery of the world’s most aerodynamically questionable dog.

The “Evolutionary Oopsie” Hypothesis

This first theory suggests the corgi’s short legs are what scientists call a “vestigial trait”—a leftover bit of anatomy whose original purpose is long gone, like the wings on an ostrich or the tiny, useless legs on a whale. In this view, the corgi is basically walking around on evolutionary hand-me-downs. To understand this, we must first consult the original poster child for perplexing limbs.

The OG of Awkward Arms, Tyrannosaurus Rex

The T. rex was the undisputed king of the dinosaurs, a 45-foot-long murder machine with a five-foot skull full of bone-crushing teeth. And attached to this behemoth were… three-foot-long arms. This is the anatomical equivalent of a six-foot-tall person having five-inch arms. The first paleontologist to find them, Barnum Brown, literally thought they must have belonged to a different, much smaller, and far more embarrassing animal.

For a century, scientists have tried to figure out what these arms were for. Were they used to awkwardly grip mates? To push the dinosaur up off the ground like a failed push-up? To tickle their prey into submission? Most of these theories have been dismissed as “untested or impossible,” because while the arms were weirdly strong (capable of bench-pressing 400 pounds), they had a pathetic range of motion and couldn’t even reach the dinosaur’s own mouth.

This has led many to believe the arms were just shrinking away because they were useless. But a newer, much more metal theory suggests the arms shrank on purpose: to avoid being accidentally (or intentionally) ripped off when a pack of T-Rexes descended on a carcass. Imagine a bunch of giant heads with steak-knife teeth tearing into a meal. Long, flailing arms would be a liability, easily bitten off in the frenzy, leading to a very messy and fatal case of dino-sepsis. The T-Rex’s arms weren’t useless; they were a safety feature.

The Glorious Genetic Glitch

Unlike the T-Rex, the corgi’s low-rider status isn’t the result of gradual evolution, but of a single, glorious genetic copy-paste error. The culprit is an extra copy of a gene called Fibroblast growth factor 4 (FGF4), which is in charge of bone growth. This little slip-up in the genetic code results in chondrodystrophy—a fancy term for dwarfism that gives corgis their signature short, stout legs.

This trait is dominant, so you only need one copy of this “shorty gene” to get the desired effect. And after centuries of humans saying, “Aww, look at the little legs!” and selectively breeding for them, this genetic “error” is now a permanent feature. There are no longer any purebred Pembroke Welsh Corgis without this form of dwarfism.

But here’s the catch, the fine print on the genetic contract. That same FGF4 retrogene that creates the adorable stumps also causes a serious condition called intervertebral disc disease (IVDD), predisposing these dogs to debilitating back problems. So, the corgi’s most celebrated feature is also its greatest vulnerability—a feature with a built-in bug, a deal with the evolutionary devil that we humans happily signed for them.

From Ankle-Biter to Influencer

The final nail in the “Evolutionary Oopsie” coffin is the corgi’s original résumé versus its current job description. Corgis were bred in the Welsh hills to be all-purpose farm dogs, but their specialty was herding cattle. They are “heelers,” which means they’d run behind cows and nip at their heels to get them to move. In this line of work, being short wasn’t a bug; it was a feature. When an angry cow kicked back, the hoof would sail right over the corgi’s head—a brilliant, life-saving design.

But let’s be honest, most modern corgis aren’t dodging hooves. They’ve traded the rugged Welsh terrain for plush carpets and hardwood floors. The fencing of pastures and modern transportation made their original job obsolete. Their primary role has shifted from farmhand to footstool, from nipping heels to napping on laps. For this new, cushy lifestyle, long legs would work just fine.

This makes the corgi a living, breathing relic. It’s a creature perfectly adapted for a job that, for most of them, no longer exists. Its entire body is a monument to a bygone era, maintained not by need, but by our desire for cute, loaf-shaped dogs. The “T-Rex arms,” in this light, are just the most obvious part of a body plan whose purpose has been lost to time.

The Gravitational Anchor Hypothesis

But what if we’ve been looking at this all wrong? What if the corgi’s legs aren’t a mistake, but a masterpiece? This brings us to the Gravitational Anchor Hypothesis, which posits that the corgi is a perfectly engineered, low-profile stability machine.

An Introduction to Corgi-dynamics

To understand this theory, you need to grasp two basic principles of physics: an object’s stability is determined by its center of gravity and its base of support.

- Center of Gravity (CG): This is the imaginary point where all of an object’s weight is concentrated. The lower the CG, the more stable the object. It’s just harder to tip something over when it’s already close to the ground.

- Base of Support: This is the area between an object’s contact points with the ground. A wider base makes you more stable.

The corgi’s body is a masterclass in optimizing these principles. Its stubby legs give it an incredibly low center of gravity. Its long, loaf-like body creates a wide, stable base. This isn’t a flaw; it’s the same design principle used by sumo wrestlers, who adopt a wide stance to become immovable, and by high-performance race cars, which are built as low as possible for stability in high-speed turns. The corgi isn’t a poorly designed dog; it’s a four-legged sports car built for maximum traction and unwavering stability.

The Proof is in the Sploot

The evidence for this hypothesis is all around us, most notably in the corgi’s signature move: the “sploot.” This isn’t just a cute stretch; it’s a deliberate, high-level physics maneuver. When a corgi sploots—lying flat on its belly with its hind legs splayed out like a frog—it is achieving a state of perfect physical harmony.

- It lowers its center of gravity to the absolute minimum.

- It expands its base of support to near-infinity, making it physically impossible to tip over.

- It presses its less-fluffy belly against a cool surface for maximum thermodynamic heat exchange.

The different documented forms of the sploot—the “full sploot,” the “half sploot,” and the “side sploot”—are not random. They are clearly different levels of “gravitational commitment,” each posture finely tuned for the desired level of stability and cooling. This re-frames a quirky behavior as a conscious act of engineering genius. Even their occasional “bunny hop” run be seen not as a flaw, but as a “Dynamic Stability Recalibration” maneuver, designed to keep their CG perfectly aligned for maximum forward thrust.

An Insult to Engineering

This brings us back to the T-Rex. The Gravitational Anchor Hypothesis demands that we reject this lazy comparison. Yes, both have short arms relative to their bodies, but that’s where the similarity ends. The T-Rex’s arms were non-load-bearing accessories, functionally useless for movement.

A corgi’s front legs, however, are the main event. They are the load-bearing pillars of the entire structure, supporting roughly 55-60% of the dog’s body weight. They are essential for every single movement, from a walk to a full-blown, high-speed gallop.

The resemblance is a classic case of convergent evolution: two unrelated species evolving a similar trait to solve two very different problems. The T-Rex’s problem was “How do I not get my arms ripped off by my hungry friends?” The corgi’s problem was “How do I not get my head kicked into next week by this cow?” The solution for both? Shorter limbs. They aren’t twins; they’re just two geniuses who arrived at the same brilliant answer from different directions.

- Tyrannosaurus rex

- Relative Size: ~3 ft long on a 45 ft body; highly disproportionate

- Musculature: Shockingly buff; could bench press 400 lbs

- Range of Motion: Pathetic; ~45-degree swing; couldn’t even high-five itself

- Primary Function: Disputed; theories include awkward mating or not getting eaten by friends

- Load-Bearing Capacity: Zero. Strictly decorative.

- Pembroke Welsh Corgi (C. familiaris)

- Relative Size: Proportionally short due to a glorious genetic glitch (FGF4 retrogene)

- Musculature: The main engine; built for locomotion and supporting a dense, fluffy body

- Range of Motion: Fully functional for all standard doggo movements

- Primary Function: Locomotion, stability, digging, and achieving maximum sploot

- Load-Bearing Capacity: Carries ~55-60% of the entire loaf’s weight

So, What’s the Deal with the Stumps?

After all this highly scientific analysis, we are left with two perfect, yet contradictory, explanations. Is the corgi an evolutionary accident, a relic of a bygone era, walking around on legs designed for a job it no longer has? Or is it a biomechanical masterpiece, a creature engineered for unparalleled stability, demonstrating its mastery of physics with every sploot?

The answer, of course, is yes.

The corgi is not one or the other. It exists in a state of quantum superposition. It is a “Quantum Fluffadox.” A random genetic mutation, preserved for an ancient herding job, just so happened to create a body plan that is an accidental marvel of engineering. The evolutionary oopsie produced a work of art.

The corgi is a walking, splooting paradox that defies easy explanation. It is a testament to the weird, wonderful, and often hilarious ways that evolution and human preference can collide. Clearly, more research is needed. We hereby call for the immediate establishment of the “International Institute for Applied Corgi-dynamics” and humbly request grant funding to purchase several research subjects, a slow-motion camera, and a variety of cool floor surfaces. For science.

Follow Our Corgi Adventures!

Pinterest

Instagram

TikTok

YouTube