Corgi Cosmonaut: The Shocking Truth About Space's Shortest Explorers

Published: 2025-08-05

Can a corgi become an astronaut?

Disclaimer: This blog post is a purely hypothetical and satirical exploration of a beloved breed in an extraordinary setting. Under no circumstances should any animal, especially a Corgi, be subjected to the rigors of real-world spaceflight. Their safety, well-being, and adorable waddles are best kept firmly on Earth. This discussion is for fun, facts, and a healthy dose of ‘what if’ – not actual space dog recruitment!

Introduction: The Cosmic Corgi Dream

Could a fluffy, low-riding Corgi conquer the final frontier? This semi-scientific deep dive explores the hilarious and complex realities of sending the beloved four-legged loaf into orbit. We’ll examine the physiological and psychological hurdles, seasoned with satirical “what-ifs,” to determine just how good a Corgi astronaut could really be. Prepare for a journey where scientific facts meet delightful absurdity.

The Corgi Profile: Earth’s Most Unlikely Astronaut?

The journey begins by assessing how the Corgi’s unique traits, so endearing on Earth, might fare in the unforgiving vacuum of space.

Physical Traits: A “Low-Rider” Analysis for Space Travel

Corgis are identifiable by their short stature, prick ears, and foxy face . They have firm, level toplines, deep chests, short forearms, and strong hindquarters . Typically weighing 23-28 pounds and standing 10-12 inches tall, their compact size might seem advantageous for a cramped capsule . However, their “low-rider” build and short, bowed legs are fundamentally designed for terrestrial locomotion, not zero-G maneuvers .

A critical detail is their “chondrodysplastic” nature, meaning slightly bowed limbs and a significant predisposition to back problems . Their longer-than-tall, straight back, while adorable, presents unique challenges for space. The inherent structural vulnerabilities of a Corgi’s spine, specifically their predisposition to Intervertebral Disc Disease (IVDD) and Degenerative Myelopathy (DM), would be catastrophically exacerbated by spaceflight’s physical stresses. These conditions involve spinal compression, nerve degeneration, and progressive mobility loss. The immense G-forces during rocket launch and re-entry would exert compressive forces on their susceptible intervertebral discs, potentially triggering acute herniations or accelerating degenerative processes. Prolonged microgravity would further weaken spinal support through rapid bone demineralization and muscle atrophy. This combined assault would make their return to Earth’s gravity not just painful, but highly likely to result in permanent paralysis or severe, debilitating mobility issues. This represents a fundamental biological mismatch; a Corgi’s anatomical predispositions make them uniquely ill-suited for space travel, transforming a whimsical idea into a serious welfare concern.

Temperament & Intelligence: The “Big Dog in a Small Body” in a Tiny Spaceship

Corgis are known for their quick intelligence and forceful will; they are active, animated, and famously do not want to be left out of any action . They possess a “big dog in a small body” mentality, often described as tenacious, bold, and protective . While intelligent and willing to learn, they frequently have “a mind of their own” and can be manipulative if not trained with a firm but kind hand . They are also prone to excessive alarm barking if left alone too much or not exercised enough . Despite their size, they are athletic and excel in activities like herding and agility, demonstrating their love for working with people and enjoying training .

While their intelligence and trainability are positives, their “forceful will” and “big dog in a small body” attitude might lead to hilarious (and potentially disastrous) insubordination in orbit. Imagine a Corgi attempting to “herd” floating astronauts or barking indignantly at every cosmic ray. Their inherent need for constant activity and family inclusion would make prolonged confinement in a tiny capsule a nightmare for both the Corgi and its human crewmates. The Corgi’s strong social needs, active and independent nature, and inherent “forceful will” directly contradict the requirements of extreme, prolonged confinement and rigid routines within a spacecraft. Historical accounts confirm that even docile dogs struggled significantly with extreme confinement, becoming restless and exhibiting physiological deterioration, with long periods of specialized training required for adaptation. Space missions demand strict discipline, predictable behavior, and adaptability to severe environmental constraints. Unlike the “quiet” and “balanced” dogs favored by Soviet researchers a Corgi’s strong personality would likely manifest as severe behavioral distress. This could include incessant vocalization that interferes with communications, destructive behaviors targeting equipment, or even refusal to cooperate with essential systems like feeding. Their intelligence might become a double-edged sword, enabling them to find creative (and disruptive) ways to express displeasure. The psychological and behavioral compatibility of an animal is as crucial as its physiological resilience for space travel. A Corgi’s temperament, while endearing on Earth, makes it a poor candidate for the psychological rigors of a space mission, highlighting the critical importance of behavioral selection.

The Launchpad Leap: Surviving the Ascent

The journey to space is fraught with challenges, particularly the intense forces and sensory overload of a rocket launch. How would a Corgi cope with such an ordeal?

G-Force Gala: The Squished Corgi Phenomenon

Rocket launches subject living organisms to immense G-forces, causing rapid spikes in heart rate and respiration. Historically, animal astronauts faced extreme conditions: Laska, a mouse, endured a staggering 60G with an unsuccessful outcome. Laika, the first dog in orbit, experienced her heartbeat triple and breath rate quadruple during a 5G launch. While smaller animals might have a higher threshold, the direction and rate of change of G-force are critical factors .

Imagine a Corgi, strapped snugly into its custom space harness. As engines ignite and the rocket thunders skyward, its low-slung body would become even lower, a furry pancake of pure determination. Its intelligent expression would morph into a wide-eyed, jowly masterpiece of G-force distortion, ears plastered back. While G-forces challenge any organism, a Corgi’s spinal vulnerability makes it uniquely susceptible to catastrophic injury during launch. The physiological stress observed in other space dogs would be compounded by this breed-specific weakness. The rapid onset and intense compressive pressure of launch G-forces would act as a direct trigger for acute IVDD episodes in a Corgi. This is about the very real likelihood of immediate and irreversible spinal cord compression, leading to paralysis, severe pain, and potentially catastrophic outcomes. The humorous image of a “squished Corgi” masks a profound medical emergency, highlighting a critical aspect of biological compatibility for space travel.

Noise & Vibration: A Symphony of Stress (and Barks)

Rocket launches are characterized by incredibly intense noise and vibration, well-documented stressors for animals. These can damage auditory systems, degrade performance, modify physiological functions, and induce significant distress. Effects can be immediate, like mechanical degradation of visual acuity, or cumulative, leading to fatigue. Laika, for instance, was explicitly noted as “terrified” by the noises and pressures of her flight.

A Corgi, famously prone to “excessive alarm barking” at a mailman, would undoubtedly find the rocket’s roar a personal affront. Imagine engine thrust competing with indignant “WOOFS!” echoing through the capsule, perhaps a new, high-pitched “space bark.” The constant, intense vibration might turn their short legs into a furry blur. Given their predisposition to vocalization and reliance on acute hearing, a Corgi would likely experience the launch environment as an overwhelming auditory assault. This would trigger an intense, sustained stress response, leading to panic, increased heart rate, and further physiological strain. The “alarm barking” could escalate into a self-perpetuating cycle of anxiety and distress, impacting their ability to cope with other stressors. While all animals experience stress from launch noise and vibration, a Corgi’s specific behavioral trait and highly developed senses suggest a disproportionately severe psychological and physiological reaction, adding another layer of unsuitability for spaceflight.

Confinement Conundrum: The Corgi’s Capsule Claustrophobia

To prepare animals for spaceflight, researchers subjected them to prolonged confinement. Dogs for Sputnik 2 were kept in progressively smaller cages for up to twenty days, causing restlessness and general deterioration. Only long periods of dedicated training adapted them to these conditions.

A Corgi, a breed that “wants to be part of the family” and “does not do well left in kennels” , would find a tiny space capsule the ultimate affront to its “forceful will”. One can envision it attempting to “redecorate” the capsule with its teeth, staging a dramatic, albeit short-legged, escape attempt, or simply refusing to acknowledge the “space kennel.” The Corgi’s strong social needs, active and independent nature, and inherent “forceful will” directly conflict with the demands of extreme, prolonged confinement in a spacecraft. Unlike the “quiet” and “balanced” dogs favored by Soviet researchers a Corgi’s strong personality would likely manifest as severe behavioral distress. This would not only be detrimental to the Corgi’s well-being but also pose a significant operational challenge for the crew, potentially leading to excessive vocalization, destructive chewing, or active resistance to essential systems like feeding. Beyond physical adaptation, psychological resilience to isolation and confinement is a critical, often underestimated, factor for successful space travel. A Corgi’s temperament makes it a poor candidate for the psychological rigors of a space mission, highlighting the profound importance of behavioral and psychological profiling in astronaut selection.

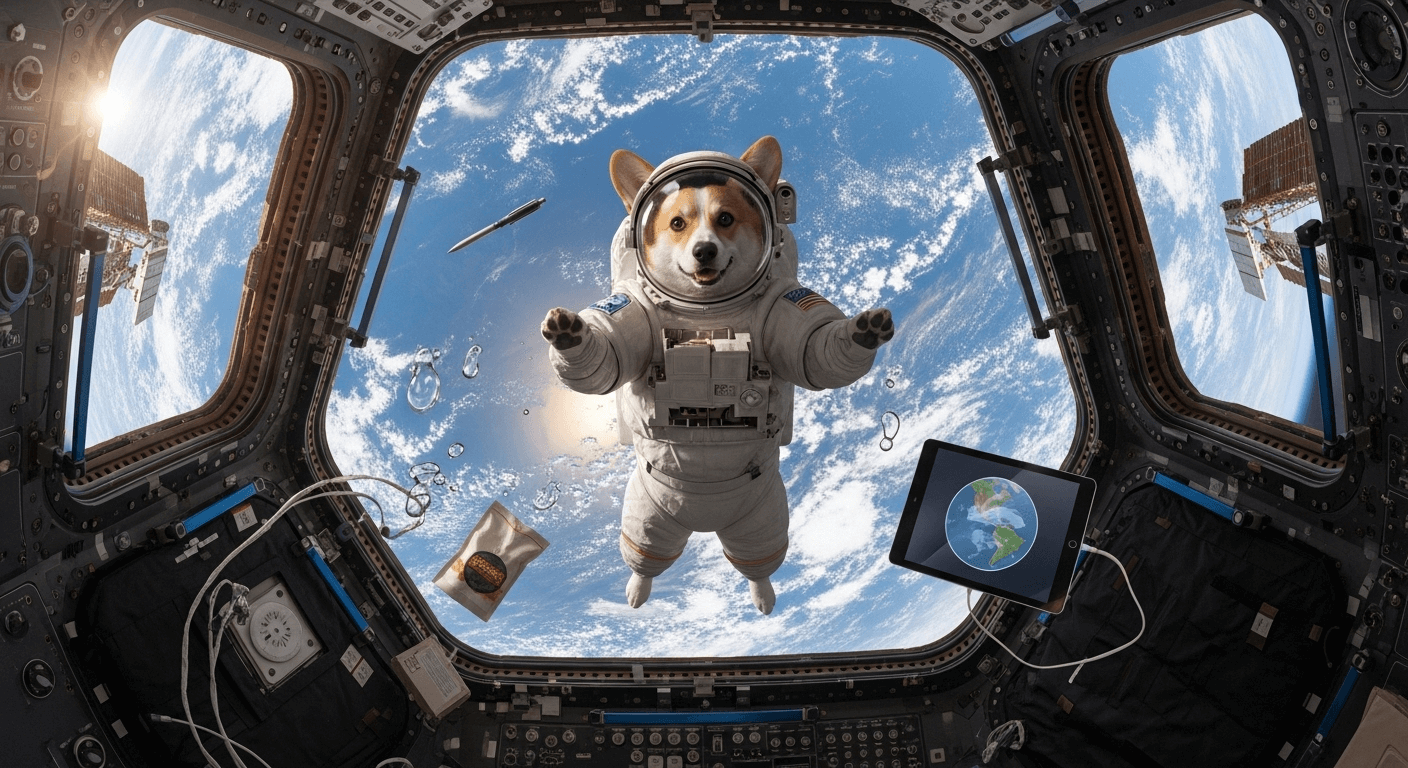

Zero-G Zoomies: Life in Orbit

Assuming a Corgi miraculously survived the tumultuous ascent, the next challenge would be adapting to life without gravity. How would a creature so fundamentally tied to the ground navigate the boundless freedom of microgravity?

Microgravity Mayhem: The Floating Loaf

Life in zero-gravity profoundly impacts physiology. It removes gravity’s normal loading effects on the cardiovascular system, leading to ‘aging-like’ deconditioning, loss of physical fitness, decreased circulatory blood volume, reduced cardiac contractility, and significant bone density loss. Dogs are “cursorial” animals, evolved for walking and running on the ground. Experts suggest zero-gravity is a “horrible idea” for them as they “wouldn’t be able to cope with a free-fall environment,” unlike humans who adjust more easily. In low-G, dogs would likely become leaner and more flexible but would inevitably suffer bone density loss and weaker cardiac systems, making a return to higher gravity painful.

Picture a Corgi, built for low-to-the-ground herding and power-splooting, suddenly experiencing weightlessness. Would it be graceful, gliding like a furry sausage, or a chaotic, flailing torpedo ricocheting off bulkheads? “Corgi Zoomies” would elevate to a cosmic level, with accidental headbutts to sensitive equipment and bewildered attempts to “sploot” mid-air. The idea of them becoming “lean, gracile, and flexible” in low-G is humorously at odds with their stout terrestrial form. A Corgi’s musculoskeletal and cardiovascular systems are inherently designed for gravity-dependent movement. In microgravity, their powerful, short legs and strong hindquarters , effective for herding on Earth, would be largely useless for propulsion or controlled movement. This lack of functional load would lead to rapid and severe muscle atrophy and bone demineralization , far beyond what might be observed in humans. Their inability to effectively navigate or stabilize themselves in free-fall would be frustrating and could lead to injury from uncontrolled collisions. The fundamental evolutionary design of a Corgi is antithetical to a microgravity environment. A Corgi’s profound inability to cope would make basic navigation, self-care, and even simple existence extremely challenging, highlighting the deep impact of gravity on species-specific locomotion and physiology.

The Gravity Bias Gap: When Treats Don’t Fall “Down”

Fascinating research reveals that domestic dogs do not possess a human-like “gravity bias.” Unlike young children, who instinctively expect dropped objects to fall straight down, dogs do not systematically search for dropped objects directly beneath the drop point. Instead, they tend to begin their search in the center of an apparatus before widening it, only successfully locating treats if the tube is transparent, allowing visual tracking. This suggests dogs have differing opportunities to learn about gravity compared to humans.

Imagine a Corgi trying to play fetch in space. A tossed squeaky toy floats away instead of arcing downwards. The Corgi, expecting it to fall “down,” would look utterly bewildered, tilting its head in that classic confused pose, searching frantically for the “missing” toy on the floor that isn’t there. The frustration of a Corgi whose world no longer adheres to gravity’s fundamental laws would be both scientifically fascinating and comically tragic, potentially leading to existential canine crises. In a zero-gravity environment, where “down” is relative and objects behave unpredictably, a Corgi’s lack of a gravity bias would lead to constant cognitive disorientation and profound frustration. This extends to their ability to navigate, interact with objects, and understand their own movements. Such persistent cognitive dissonance could significantly increase a Corgi’s stress levels, leading to chronic anxiety, impaired learning, and diminished capacity to perform tasks. This would make them highly impractical and distressed crewmates, highlighting how deeply ingrained gravitational understanding is to a species’ interaction with its environment.

Re-entry & Landing: The Return to Terra Firma

The journey is not over until the Corgi is safely back on solid ground. Re-entry and landing present formidable challenges, potentially undoing any miraculous survival thus far.

The Fiery Descent: A Corgi’s Crash Landing

Re-entry into Earth’s atmosphere involves significant deceleration forces, comparable to launch G-forces. The landing itself can also involve considerable impact. Historical animal flights underscore the danger: early missions often resulted in unsuccessful outcomes upon impact if proper re-entry strategies were not fully developed, as seen with Albert II, Laika (due to heat shield loss), and mice in the MIA project. Successful returns, such as those of Soviet dogs Dezik and Tsygan, relied on sophisticated systems like hermetically sealed containers recovered by parachute.

After miraculously surviving the vacuum and zero-G zoomies, the Corgi astronaut faces the ultimate test: returning to Earth. Its short, bowed legs would brace for impact, perhaps attempting a “sploot-landing” for maximum surface area distribution. The “fiery descent” would be less about re-entry plasma and more about the Corgi’s intense desire for its favorite squeaky toy and a well-deserved belly rub. The Corgi’s spine would have already been severely stressed by launch G-forces. Furthermore, prolonged microgravity would have led to significant bone and muscle deconditioning, weakening spinal support structures. The re-entry and landing phase would deliver a

cumulative and potentially devastating blow to a Corgi’s already compromised spinal system. The intense deceleration forces, combined with the inevitable impact of landing, would act on a skeletal and muscular system already weakened and potentially pre-damaged. This multi-faceted assault would almost certainly trigger severe, acute IVDD, leading to immediate paralysis, catastrophic spinal injury, or excruciating pain, making a safe and functional return to Earth’s gravity highly improbable. The notion of a “graceful landing” for a Corgi astronaut would be anything but, highlighting the profound and lasting physical consequences of space travel on an anatomically predisposed animal.

Long-Term Effects: The Post-Flight Paw-sitron

Even when animals survived spaceflight, researchers observed significant long-term physiological and behavioral changes. For example, Otvazhnaia, a Soviet dog hailed as a “professional cosmonaut,” became reluctant to leave her kennel and play with other dogs after her fifth flight, despite normal physical tests. She only gradually returned to her confident self over several months. Scientists recognized these effects would carry over to humans, informing early human spaceflight protocols. Beyond behavioral changes, spaceflight can lead to lasting cardiovascular dysregulation, continued bone density loss, and even DNA damage.

Assuming the Corgi miraculously survived its cosmic adventure, what would life be like post-flight? Would it suffer from perpetual “space-lag,” constantly trying to float to the treat jar or barking at phantom zero-G dust bunnies? Would its barks now have a slight, otherworldly echo? One might humorously speculate on its post-astronaut career, perhaps as a motivational speaker for other Earth-bound pups, or a connoisseur of gravity-bound naps. The extreme psychological stressors of spaceflight – including intense noise and vibration during launch, prolonged confinement, isolation, cognitive disorientation of microgravity, and the sheer alienness of the environment – would likely inflict profound and lasting psychological trauma on a Corgi. Even if physical injuries healed, the Corgi’s inherent temperament and social needs suggest it would struggle immensely with post-flight adaptation, potentially developing chronic anxiety, altered social behaviors, or a form of canine PTSD. The observed changes in Otvazhnaia would likely be amplified in a Corgi. The success of a space mission for a living organism is not just measured by physical survival; it is crucially about the quality of life and functionality post-flight. The long-term psychological well-being of animal astronauts is a critical ethical and practical consideration. A Corgi’s specific temperament suggests it would struggle immensely with these long-term adaptations, highlighting that psychological resilience is as vital as physical endurance for cosmic journeys.

The Verdict: Why Corgis Are Best as Terrestrial Trailblazers

This semi-scientific journey has revealed the overwhelming (and comically tragic) scientific hurdles facing any aspiring Corgi cosmonaut. From their predisposed spine battling extreme G-forces and microgravity’s deconditioning effects, to their vocal nature competing with rocket noise, their need for activity clashing with confinement, and their fundamental lack of gravity bias in a floating world – the challenges are immense.

The squished Corgi during launch, the cosmic barks echoing through the cabin, and the perpetual search for a “down” that does not exist. These scenarios, while amusing, underscore the profound biological and behavioral mismatches between a Corgi and the cosmos.

Let it be reiterated, with all due seriousness (and a wink): this was a purely imaginative exercise. The well-being of beloved Corgis is paramount. Their rightful place is on laps, frolicking in parks, or ruling the living room – not in orbit.

Let us celebrate the Corgi for what it truly is: a perfect, gravity-loving companion. Their true mission, far more noble and achievable, is to bring boundless joy, shed copious amounts of fur, and occasionally herd ankles right here on Earth. Here, their short legs and long backs are perfectly adapted for chasing squirrels, herding dust bunnies, and reigning as the undisputed royalty of the terrestrial realm. Perhaps one day, with advanced genetic manipulation that transforms them into lithe, long-limbed space-adapted canines a truly space-faring dog might be seen. But for now, let us keep our Corgis grounded and glorious.

Follow Our Corgi Adventures!

Pinterest

Instagram

TikTok

YouTube